In this second article explaining the SNAPP framework’s five principles I will focus on the importance of social norms (click here to read about simplicity). This principle includes social proof and the reasons we imitate others, social and cultural norms, human trust and reciprocity, the role of context and the importance of humanizing behaviour change.

Social proof and imitation

We all tend to follow and copy the behaviours of other people, especially those we are closer to. Similar behaviours signal acceptance and a shared identity. For example, one of the strongest predictors of a household installing solar panels is whether the neighbours have them (especially when they are visible).

People are more likely to “do the right thing” when we believe we are being watched, and donations for causes like the environment increase when they are “public”. As George Washington wrote in 1780, “Example, whether it be good or bad, has a powerful influence”. We have seen the power of social imitation all too visibly in recent days!

A great example of this is the introduction of escalators on the London Underground, who had to get an employee who had lost a leg to ride up and down the escalators for a whole day in order to encourage others to use them.

Studies of social networks have shown that health behaviours are contagious and being closely connected is predictive of future behaviour changes and health outcomes. Social norms can also be leveraged to encourage healthy behaviours. In a huge study of hand washing habits (pre-Covid), normative messages were consistently good at increasing rates of hand washing for both men and women (you can guess which were better without any messaging).

Negative social proof

In one interesting experiment, Robert Cialdini worked with park rangers to try and stop visitors removing pieces of petrified wood at a national park. They found that a social proof message backfired. Saying that, “Many past visitors have removed the petrified wood from the park, changing the natural state of the forest”, increased the number of thefts as the message merely normalized the behaviour. A simple request, “Please don’t remove the petrified wood from the park, changing the natural state of the petrified wood”, was much more effective.

More recently, there was some consternation when a national newspaper in the UK published the headline, “Fifth of staff in some care homes refuse Covid vaccine believing they are ‘invincible’”. It was rightly pointed out that it would be much better to emphasise the vast majority of people who were taking the vaccine. Similarly, an older campaign to encourage people to give blood, made a mistake when they used the headline, “Only 4% of people give blood”.

Sometimes social norms are more about perceptions than reality. A recent research study looked at attitudes to labour force participation in Saudi Arabia. In 2017, women had a labour force participation rate of 18%, and anecdotally this was because it was a “social norm”. However, the research revealed that the majority of men supported women’s participation but believed that other men did not. When given the correct information, behaviours changed.

Social norms, identity and behaviour

Social norms can be descriptive or proscriptive (injunctive) and recent studies show that descriptive norms work best across different cultures and a good example is a large-scale study of voter turnout in Michigan (USA) which measured the voting behaviour of 180,000 households in 2006, using mailings with different descriptive headlines (including a control panel):

- Do Your Civic Duty and Vote!

- You Are Being Studied! (aka Hawthorne effect)

- Who Votes is Public Information!

- What if Your Neighbours Knew Whether You Voted?

To cut a long story short, the description of neighbour’s voting behaviour had the most powerful impact on other people’s voting behaviours.

Such approaches have been used widely in environmental messaging, and Robert Cialdini has tested the impact of norms versus environmental concern led messages, and separately how different kinds of norm have different impacts (i.e., which normative groups are most persuasive).

In an initial experiment he tested to messages:

- “Help to save the environment”

- “Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment – 75% of the guests are already reusing their towels“

Social norm messages were more effective than environmental messaging, despite the expectations that behaviours are driven by environmental concerns.

In a second experiment, Cialdini looked at how social identity influenced the types of norms that people would follow. He tried a number of different messages:

- “Help to save the environment”

- “Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment. In a study 75% of the guests reused their towels.” (Guest identity)

- “Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment. In a study 75% of the guests in this room reused their towels.” (Same Room identity)

- “Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment. Join your fellow citizens.” (Citizen identity)

- “Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment. In a study 76% of women & 74% of men reused their towels.” (Gender identity)

The most effective messaging was the “same room identity” messaging, with a very specific context.

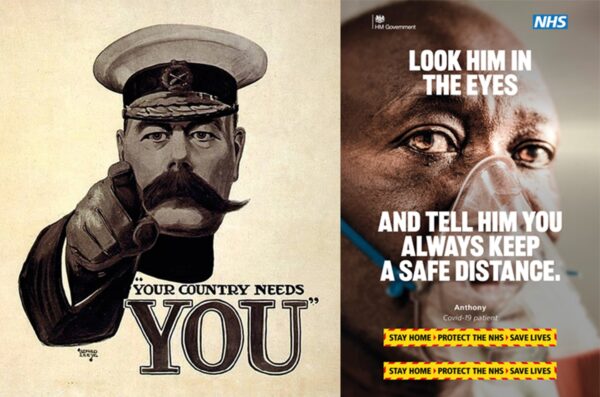

Humanising behaviour

We are all human, and a human touch is often more effective than any other kind of behavioural intervention. For example, reciprocity is a powerful social norm governing in-kind exchanges between people. For example, when a restaurant gave diners a single sweet with their bill, tips increased 3.3%. When they gave them two sweets, tips increased by 14.1%!

This is a common technique of charity solicitation letters which include a small gift, or hospitals, colleges, and universities asking former patients and students for donations. Robert Cialdini talks about the ‘door-in-the-face’ technique, when a person makes an initially large request followed up by a smaller request if the initial one is denied (with much more chance of success).

Applying the human touch also includes using different types of messenger, using humans (eyes, faces, smiles, people), non-verbal cues, emotional triggers, and provoking curiosity. Some interesting experiments show that people are much more likely to hand in a lost wallet if it has a picture in it (babies and pets do best). And people are more likely to contribute and cooperate if they feel they feel they are being watched.

In Martin and Marks book Messengers, they highlight two distinct types of messenger with a number of categories within them. Hard messengers work more on the basis of ‘authority’ (in its loosest sense), typically because of fame and recognition, expertise and experience, power and superiority, or attractiveness and beauty. Soft messengers work more on the basis of ‘likeability’ and ‘relevance’, typically because of personal warmth, vulnerability and openness, trust and principles, or charisma and vision.

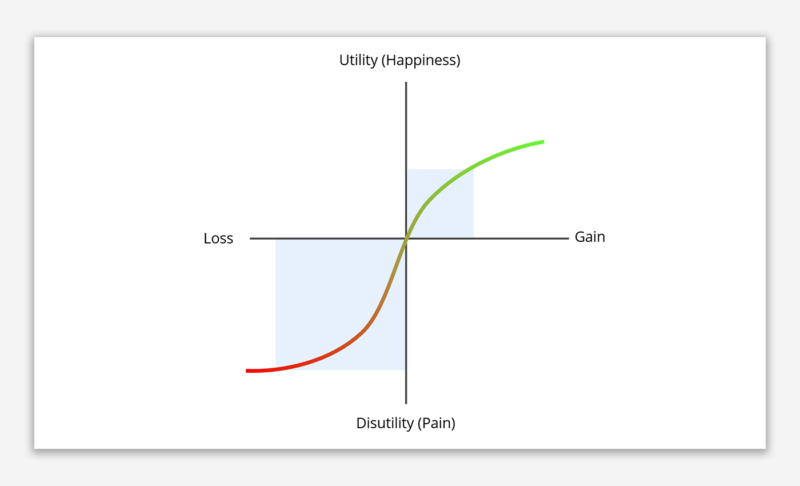

Dan Ariely famously said that, “Money is very often the most expensive way to motivate people. Social norms are not only cheaper, but often more effective as well.” In his famous study of late arrivals at children’s day care centres, introducing a fine for late arrival actually doubled the number of late arrivals. In classic economics, a penalty for late arrival is an incentive to arrive on time but in the real world punctuality was based on a social norm, and once the fine broke the norm, the fine was merely a ‘price to be paid’.

The importance of context and the Fundamental Attribution Error

In a well known ‘Good Samaritan’ experiment, researchers looked at the impact of situational and personality variables on helping behaviour in an emergency situation. They studied people going between two buildings who encountered a shabbily dressed person slumped on the side of the road.

Some of the subjects were going to give a short talk on the parable of the Good Samaritan, while others were going to give a talk on another topic (not relevant to helping behaviour). The subject of their talk made no difference to the likelihood of someone stopping, and neither did religious personality variables. What did make a difference, is that subjects who were in a hurry to reach their destination were much more likely to pass without stopping.

This finding is consistent with the Fundamental Attribution Error, which highlights that we over-emphasise personality and trait-based explanations of behaviour and underplay situational influences. This is particularly true in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) cultures. Studies show that personality traits generally have no correlation with behavioural outcomes.

There are two over-riding lessons from these findings, Firstly, social norms are often the best way to motivate behaviours. Secondly, focus on the context (environment, social situation, culture) as much as if not more than the people themselves if you want to change behaviours.

Making It PERSONAL and Relevant (Part 1 – Loss aversion) – TapestryWorks

[…] heuristics and SNAPP we focus on all things personal (click for previous articles on simplicity, norms and availability). The use of plastic is a huge issue for sustainability. Some countries (and […]