“At Christmas play and make good cheer, For Christmas comes but once a year” (Thomas Tusser)

Although winter celebrations had been a part of people’s lives for millennia (at least in the Northern Hemisphere where it marked the turning of the year), many of the traditions of modern Christmas were inspired by two literary works. C.S. Lewis wrote in 1957 that there were three versions of Christmas: religious festival, merry holiday and commercial racket, and while the first two go back long before modern times, the last can definitely be blamed on these two works.

A Visit from St Nicholas (known by most people by its first line “’Twas the night before Christmas”) was first published anonymously in 1823, and finally attributed to Clement Clarke Moore in 1837 (although there is some evidence that others contributed to the poem). It is is the best known poem in English, and had a huge impact on Christmas traditions in America and beyond, especially after it began to be reprinted in newspapers and journals a few years after being written.

Specifically, The Night Before Christmas shaped modern conceptions of Santa Claus (St Nicholas) from that time until now and also the custom of Christmas gift-giving. Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of children, among many other groups of people (including merchants!), and his Saint Day of 6 December was handily merged with traditions of midwinter celebrations.

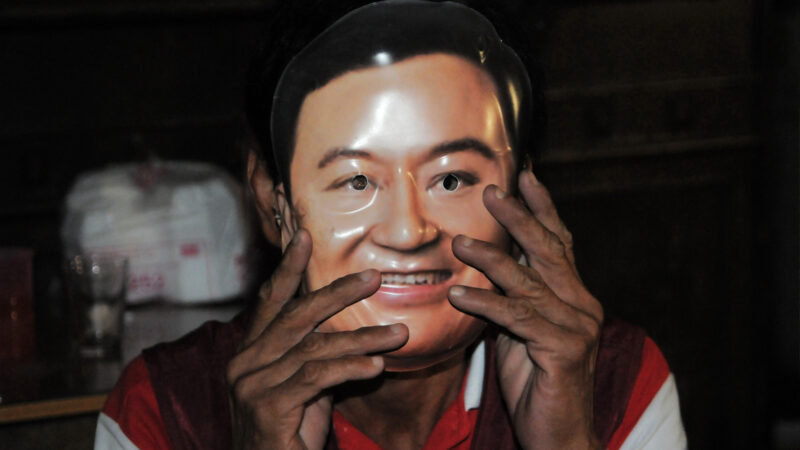

Moore’s version of Santa Claus was influenced by Sinterklaas, who is still important in Dutch culture and also parts of Belgium, Luxembourg and Northern France. Sinterklaas can be traced back to 1810, but is probably older, appearing in a poem published in New York of all places! St Nicholas was known for secret gift-giving (which he used for political influence) and this was incorporated into the figure of Sinterklaas and ultimately Santa Claus.

Modern imagery of Santa Claus started with Thomas Nast who drew versions of him from 1863 on, long before Haddon Sandblom’s Coca-Cola advertisements. The figure below is from 1881. His red robes are also a tradition of Sinterklaas and may reference the red robes of bishops in St Nicholas’s time.

Santa doesn’t appear in A Christmas Carol (originally published in 1843 as a ghost story for Christmas). However, it created many modern British Christmas traditions, which were pretty much invented by Charles Dickens as a wish list of what Christmas could and should be rather than what it actually was.

However, they did capture the Victorian zeitgeist and he was helped by Queen Victoria, whose German husband also brought many of his country’s traditions to Britain. At the start of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1837, very few British children hung stockings, knew of Santa Claus, had seen a Christmas cracker, ate turkey, gave presents or lighted a Christmas tree. And they certainly would not have had a day off. Twelfth Night was a far more important celebration in the early 19th century (and why we have Christmas cakes).

The most important influence of A Christmas Carol is the focus on family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing and the generosity of spirit that is now such an important part of the holiday in many countries. After Dickens great story, nobody would dare to speak like Ebeneezer Scrooge does, “Bah! Humbug! … Every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart.”

These two works, and many other influences, transformed Christmas from a patchwork of local and regional cultural rituals transformed into the multi-national celebration that we have today. What existed before?

The midwinter festival was celebrated long before the birth of Jesus, as a midwinter solstice, Yule (or Jul) in Northern Europe and Saturnalia in ancient Rome. Most of these festivals were essentially big Christmas parties (the merry holiday that C.S. Lewis wrote about), where people celebrated the turning of the seasons, consumed much of what had just been harvested and generally had a riot.

Midwinter solstice (meaning “when the sun stays still”) is the shortest day of the year, and the turning point in the Earth’s orbit around the sun. The Northern European festival of Yule comprised 12 days of eating, drinking, singing, joking and storytelling, and is the origins of Yule logs which were the blazing wood fires that were traditional at this time.

Yule had grim origins as a ‘slaughter night’ in mid-December, which was also the origins of the Roman festival of Saturnalia. Saturnalia was very much about debauchery and was also associated with misrule and a time of role reversal when masters and servants changed places for a while (hence the association between Twelfth Night and the “Lord of Misrule” who was the master of the revelries). Although originally from 17-19 December, Saturnalia grew into a week-long festival ending on 24 December.

Finally, what about the religious festival? The first reference to 25 December as the birthday of Jesus was in AD 354 by Valentius (although it’s a very unlikely date as the weather would be very cold in Judea, and certainly the flocks would not be outside). Eventually, Christians took over the Roman holiday of the Feast of the Undying Sun and made it their own. In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed a holiday between Christmas and Epiphany which became the twelve days of Christmas, meshing the religious festival with the merry holiday and much later the commercial racket.

Whether you are celebrating Christmas as a religious festival, a merry holiday or a commercial racket, and even if you are not celebrating it at all, have a great Christmas holiday. These lines from an TV comedy series called The Likely Lads, really sum up the spirit of Christmas:

Terry “It’s all got out of hand these days. It’s just one big racket … People over eat, over spend and over sentimentalize.”

Bob “I know, I know, I know and I love every minute of it.”

REFERENCES

The Battle For Christmas: A cultural history of America’s most cherished holiday by Stephen Nissenbaum

Christmas Past by Gavin Weightman & Steve Humphries

Christmas and the British: A modern history by Martin Johnes

A Pictorial History of Santa Claus by The Public Domain Review