The Choice Factory by Richard Shotton has been described by Rory Sutherland as a “Haynes Manual for understanding consumer behaviour”. Expectations were very high when I started reading this book (learn more about the power of expectations later in this review) and were not disappointed.

Written by an advertising professional who is also well read in the scientific literature, this book is full of real-life examples and practical tips to apply 25 principles of behaviour. He starts fittingly with The Fundamental Attribution Error, which I have often written about and consider one of the most important to understand. Let’s focus on five of the biases Richard Shotton discusses in the book.

Social Proof

Social proof is the reason why “popular brands become more popular still”. Richard Shotton highlights Robert Cialdini’s writings on social proof, including one of his most famous experiments testing alternative versions of a message left in hotel rooms encouraging occupants to use their towels more than once (something that’s now much more common). He found that a basic statement of the environmental benefits (his “control”) got 35% of guests to comply, while a more social plea (“most people reuse their towels”) encouraged 44% to comply. However, the most successful message was a more specific claim that “most people who stay in this room reuse their towels” which got 49% compliance.

Cialdini argues that relevance is a key factor in social proof (there are much more relevant claims than “people who stay in this room” in other contexts). The most interesting aspect of the experiment was that when Cialdini asked people which message would work best, the majority believed that the basis environmental message was the most powerful.

Other examples of social proof are doubling sales of a brand of beer by placing a message on the bar about “this week’s best-selling ale” and Costa Coffee talking about being popular “among coffee lovers” (very relevant for their customers). As Mark Earls has written, “We need to learn from anthropology and focus on the space between people not the space between their ears.”

Negative Social Proof

Importantly, social proof can have the opposite effect if used incorrectly. Richard Shotton cites an example of a Guardian advert, “more people are reading The Guardian than ever, but fewer are paying for it”, which effectively tells people that if they don’t pay they are in the majority.

Similar examples are an NHS Give Blood campaign publicizing that only 4% of people (so if you don’t give blood you are 96% of people) and signs in doctor’s surgeries about the number of people who miss an appointment. As he points out, it is not effective to stress that an unwanted behaviour is common, as you make it more likely. It is better in such cases to “flip the statistics”.

Habit

Richard Shotton argues that half of behaviour is habitual (I would argue much higher than this) and that such behaviour is very difficult to change. He writes that changing habits is often about “shaking people out of automatic behaviour” and has some useful tips.

The first is to target customers after important life events, when they are more likely to change their habits. Similarly, they may be more open at moments of reflection, such as “nine-enders” (people who are in the year before changing the first number in their age), who have been shown to be more likely to make changes. In other cases, he advises communicating before people’s habits harden (if possible).

Expectancy Theory

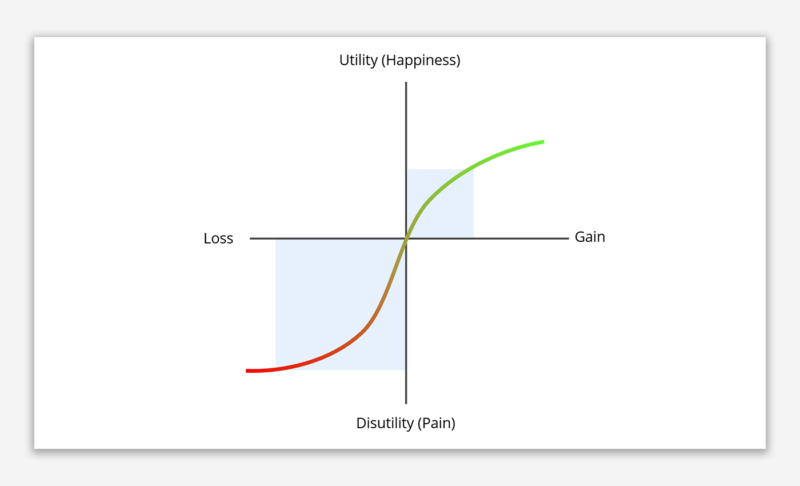

As I mentioned above, expectations shape our experience and how we perceive tehj performance of a product or service. For example (and back to beer) serving methods affect taste, and drinking beer from a plastic cup is different than drinking it from a plain glass or even a branded glass. Unsurprisingly, branded glasses lead to the best perceptions of performance, although the product is exactly the same, and the scale of this effect is inversely proportional to the size of the brand.

Presentation is as important, if not more so, as the product. Another example of expectancy effect is the impact of good copywriting on a restaurant menu. “Seafood filet” is nowhere near as tasty as “succulent Italian seafood filet”.

Richard Shotton has Veblen Goods as a separate bias, but I believe this is another example of expectancy. High prices can boost demand. Expensive wine tastes better than cheap wine and expensive painkillers (and branded painkillers) have measurably stronger analgesic effects.

The Pratfall Effect

The Pratfall Effect is less well known and one of the most interesting biases, referring to how flaws make a brand more appealing. This is similar to the well-known sales trick that confessing to a weakness before talking about your strengths increases sales, because it makes you more believable (and vulnerable).

There are several well-known advertising examples, including Guinness talking about “good things come to those who wait”, Stella Artois admitting that it is “reassuringly expensive”, and Avis advertising as the second biggest car hire company (and therefore “we try harder”). Famously, the National Dairy Council’s “naughty, but nice” campaign for cream cakes (which I remember growing up in the UK) was the work of Salman Rushdie when he worked at Ogilvy & Mather.

In summary this is a great book for anyone in branding, marketing and advertising. Its format of short chapters with theory, practice and examples makes it easy to dip into at any time. I’ve read many books about the science of behaviour and still learnt many new tricks reading The Choice Factory.

Is choice an illusion? – TapestryWorks

[…] The Illusion of Choice, Richard Shotton builds on his first book The Choice Factory (read more here) with more insights into how marketers can apply a range of heuristics, human traits and cognitive […]