“For me context is the key – from that comes understanding of everything” – Kenneth Noland

I was lucky enough to find time for some reading over the past week, with the Chinese New Year holiday. I picked a diverse range of books to read, or what I thought were diverse, but looking back there was a common thread across all of them (and others that I have recently read). They all show in their different ways the importance of context in shaping behaviour, a theme that has repeatedly come back to me ever since my time as a student.

Famously, Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel argues that the environment, and not genetic influences (or intellectual or moral), has shaped the relative success and failure of different societies throughout human history. He strongly argues that where certain societies have had advantages (for example, written language or disease resistance), that this has been an outcome of the specific geographic, climate and local influences on behaviour and culture and not driven by any genetic difference.

It is also true that cultural meaning is shaped by environment and circumstances as much as human behaviour and the evolution of local differences. There is no clearer example in cultural history of the way that context shapes meaning, than that of the writing of Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony during the siege of Leningrad in the Second World War. This is a piece of music I have always admired, and I remember first hearing live at a BBC Prom on hot summer night in London.

In Leningrad: Siege and Symphony, Brian Moynahan powerfully intertwines the narrative of the writing of the work with that of the siege itself. The siege itself is shocking in its brutality and cost to human life and dignity (in the same way that the siege of Stalingrad was). The book is gripping in showing how Stalin saw the propaganda advantage of having the symphony played in the city itself (where there were relatively few musicians left and most of them starving to death). the history of the siege and the symphony itself, created the context in which the music’s meaning is almost completely seen as a metaphor for the siege (and by extension the battle between the Russians and the Germans).

Shostakovich himself was much more enigmatic about the meaning of this and other pieces, and had an extremely variable relationship with the authorities and Stalin. In public he once said about another piece that it was “dedicated to the victims of fascism everywhere” (my emphasis) and in private is said to have talked about the 7th being about the struggle against fascism at home as much as that coming from Hitler’s advancing army. In any case, the atrocities inflicted on the Russian people by their government matched those inflicted by the Germans (although the eventual victory of the Russians was a turning point in the war).

On a much more mundane level, the meaning of ‘sweet temptations’ has changed through history and also been shaped by the different circumstances and cultures across different parts of the world. Sweets are thought to have originated in India, but spread throughout the world along with spices. Sweets are at the same time universal (we are all genetically disposed to seek the calories that sugar provides) and highly local. Tim Richardson cites the example of chocolate tastes in the UK, where Cadbury Dairy Milk reigns (which Americans find too sweet and cloying) and the US where Hershey’s is the benchmark (a product that the British find gritty and harsh).

In The Language of Food, Dan Jurafsky shows how the words we use to describe what we eat reflect our desires and aspirations and shape the way that we experience what we eat and drink. For example, adjectives used on menus change perceptions of the menu items and tend to be used in mid-price restaurants, while he shows that top-end restaurants tend to stick with more direct descriptions and never feel the need to describe any item as “real”.

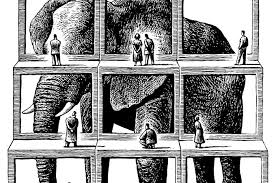

It all comes back to the importance of context. Humans are prone to overestimating the importance of individual differences and specific ‘traits’ in explaining outcomes and always underestimate the role of context in shaping how things work out (what psychologists call the Fundamental Attribution Error). In more than one recent conversation, I have been asked to explain the link between behavioural economics and semiotics. The link is obvious – behavioural science shows what cultural analysis and history has shown for a long time. Context shapes behaviour just as much, if not more than, individual differences. If you want to understand why people do what they do, start by looking around them rather than trying to get inside their head.

[Originally published in February 2015 at inspectorinsight.com]

REFERENCES

Guns, Germs And Steel: The fate of human societies by Jared Diamond

Sweets: A history of temptation by Tim Richardson

Leningrad: Siege and symphony by Brian Moynahan

The Language of Food: A linguist reads the menu by Dan Jurafsky