In this third article explaining the SNAPP framework’s five principles I will focus on the importance of mental and physical availability (read about simplicity here and norms here). This principle includes the importance of mental associations that are immediate, novel, tangible, and different, how psychological distance impacts availability, including time discounting, and the ways in which our memory is different from our experience.

Mental availability and physical availability

Robert Woodruff, President of Coca-Cola Company, famously said that Coke should be, “Always within an arm’s reach of desire.” This is a great summary of the importance of availability in shaping our behaviours, both in terms of what is readily to hand in our environment and what easily comes to our mind.

Many people overestimate the chance of dying in a plane crash and underestimate the chance of dying in a car crash (a frequent occurrence in Thailand and many other countries). This is because our estimates are based on availability in memory, and our memory is biased towards emotionally charged experiences (typically a plane crash is a big and impactful event, even if it happens very infrequently).

Standing out from the crowd

This is known as the availability heuristic (salience), and it comes in many varieties. Scarcity bias reflects that we place more value on things that are more difficult to acquire or have limited availability. In 1769, Captain Cook wanted sailors to eat sauerkraut to keep scurvy away on a long voyage, but at first the men wouldn’t eat the dish. He made sure that it was only served at the officers’ table and not available to anyone else. After one week, all sailors demanded their fair share.

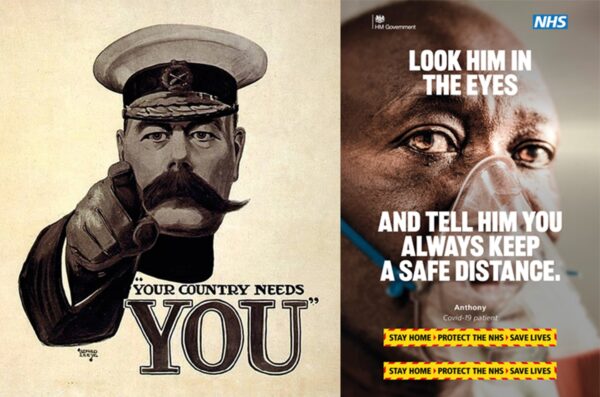

The von Restorff effect describes how some things stand out from the crowd to get noticed (e.g., the subway seat reserved for certain passengers). In one experiment, Copenhagen students painted bins brighter colours and painted footsteps leading to them in similar colours. This resulted in a 46% increase in litter going into bins, and has been replicated in UK and Australia. Similarly, when New South Wales had a problem with overdue traffic fines, they found that adding a “pay now” stamp on the top of reminder letters increased repayments up to 17% (worth $10 million per year).

In the post-Covid era it’s worth noting one idea from the Philippines that encourages handwashing. Before lunch kids’ hands are stamped with a picture of a germ which takes 30 seconds to wash off. Handwashing becomes necessary and fun!

Invoking the senses

We seek out novelty and change, making some things stand out. Similarly, we remember more recent information better and compelling, emotion-rich (and sensory-rich) descriptions make something more attractive and noticeable. In one Oxfam campaign, describing access to “clean water” increased donations relative to “bottled water”, “water”, or nothing.

Language can be used to boost plant-rich diets. Research shows that it’s best to avoid descriptors such as “meat-free”, “vegan”, “vegetarian”, “healthy”, and “low fat” as these are often interpreted as unsatisfying, restrictive, unappealing and can be viewed as ‘different from me’ (i.e., reflecting membership of an out-group).

By contrast, provenance is evocative (and is a post-pandemic trend; read more here), flavour descriptors get the mouth-watering, and invoking look and feel creates stronger appeal. When Sainsbury renamed their “Meat-Free Sausage and Mash” as “Cumberland-Spiced Veggie Sausage & Mash” in their cafes, sales increased by 76%.

Familiarity breeds liking

The recognition heuristic is the bias towards what is more familiar (as in the mere exposure effect). Gerd Gigerenzer believes that recognition is a “fast and frugal” heuristic, making best use of the limited information available to people. Recognition simplifies decision making, and often leads to more accurate inferences even with less knowledge.

Representativeness bias is our tendency to place more value of what makes a good story, and this is sometimes seen in base rate neglect when we focus on some numbers more than others. We are especially negligent of what might be representative of a whole population versus percentages and proportions which make a believable story.

The long and the short of it

The Oxford English Dictionary was announced to the world in 1860, to be ready two years late. It was finally begun in 1879. Five years later, the authors had got as far as the word ‘ant’. It was finally finished in 1928, and was already out-of-date so revisions started immediately. The planning fallacy is a common mistake that we all make. We are very bad at anticipating the future and have a very rosy view of the future (optimism bias).

The immediate and here and now always feel more immediate and ‘available’ than the distant future. Although physical distance is important (we tend to favour things which are physically close), psychological distance is also important in determining the value we place of rewards and outcomes, whether that psychological distance reflects a lower perceived chance of happening, greater social distance or events that are in the future.

Discounting time

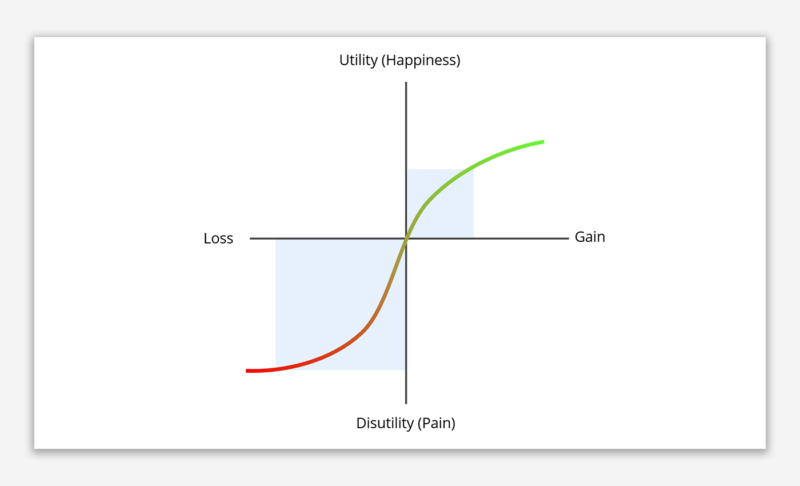

Somehow the present weighs much more heavily in our minds, and value decreases the further away in time it is. Time discounting is not linear or consistent (an effect known as ‘hyperbolic discounting’), whereas present and immediate rewards explain our impulsivity and the common need for instant gratification. This is the biggest single challenge for sustainability and other long-term problems.

Potential solutions to time discounting help people imaging the future and make it more vivid by priming future scenarios and creating mental simulations, sometimes even creating future avatars of people to trigger more realistic simulation. In effect, this is also what great storytelling does.

This has been applied to the problem of encouraging people to save money. There are many reasons why we don’t save. Savings represent a present loss (often difficult to mentally reconcile with future gains). People often procrastinate too, and often stick with the status quo to make life easier. All these reasons occur because potential future losses and gains are not vivid enough.

Imagining the future

However, people are more willing to save money a year from now than today (as the losses are far in the future). This was used to good effect in one of the better known ‘nudges’ developed by Richard Thaler and colleagues, who devised a SMarT plan as an alternative to financial planning (which most people refused). The plan involved a fixed increment of 3% additional savings for every pay raise in the future. Most people agreed to this proposal, and over multiple years ended up with higher savings rate compared with those who refused or those who made their own savings plan.

In another experiment, virtual reality (VR) was used to help people ‘imagine’ the future and identify with their future selves. Over four separate experiments, participants interacted with aged versions of themselves to encourage them to be more realistic in trading off current losses with future gains. Those who saw virtual versions of their future selves were more likely to allocate more money to the future and less to present needs.

Timing is everything

Another strategy to overcome present bias is to provide upfront incentives as well as future benefits. This is called ‘temptation bundling’, linking a ‘should’ behaviour with a ‘want’ activity to make the ‘should behaviour’ more attractive and less painful. For example, it is easier to exercise if you can watch your favourite TV show (or in my case listen to an interesting podcast).

The difference between short-term desires and long-term goals can also be a good thing, to help us imagine a set of better choices. Ordering groceries up to 5 days in advance of delivery can lead to healthier food choices, eliminating the present bias for more desirable foods. In another study, planning a week’s viewing of movies, led to more diverse choices than selecting them from day to day.

How real is time?

In the early 2000s, the management at Houston airport was dismayed by the number of passenger complaints it was receiving. The main issue was delays at the baggage carousel. Passengers were often at the end of their tether and even trivial delays tested their patience.

In response, the airport approved a hefty budget for more baggage handlers. At first, the cash looked well spent as waiting times dropped to eight minutes, about average for an airport. Complaints remained stubbornly high. The authorities considered hiring more baggage handlers but that was prohibitively expensive.

Instead, the managers took a psychological approach: they focused on improving the subjective experience rather than the objective reality. People spent about a minute walking to the carousel and eight minutes waiting. The authorities re-routed passengers after passport control so they had to walk further. This meant they spent about eight minutes walking to the carousel and just a minute waiting. Even though the time they picked up their bags was the same, complaints plummeted.

The importance of creating a single moment of joy

The Magic Castle is ranked by Trip Advisor as the second-best hotel in Los Angeles and 94% of 3,125 reviews rate the hotel as ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ (higher than Four Seasons, Beverly Hills). In reality, the hotel is basic, with dated décor, spartan suites and a small swimming pool.

But it does have a ‘Popsicle helpline’. Any time, day or night, you can pick up an old-fashioned red phone and a staff member, complete with white gloves promptly appears with a selection of ice lollies on a silver plate. An experience you will never forget. A stand-out peak moment (even better at the end)!

All these examples, show the importance of creating salience, memorability and, above all, getting noticed, either through the immediate experience of people, or by creating long-lasting and powerful memories.