In our last SNAPP article, we explored the role of loss aversion in behaviour and its potential role in behaviour change (read it here). In this article, we continue with the importance of understanding the role of the personal relevance in behaviour interventions and messaging by looking at commitment, ownership, and personal identity.

Consistency and commitment

Clocky is a brand of alarm clock outfitted with wheels, allowing it to hide itself and move around to force the owner to find it. It was invented for an industrial design class by Gauri Nanda and won the 2005 Ig Nobel Prize in Economics. The original prototype was covered in shag carpet so it looked like a pet.

Other ‘commitment clocks’ donate to causes that you hate when you ignore the alarm. Websites that make commitments public are proliferating. For example, stickK.com has more than 500,000 public commitments and over $ 50 million on the line. The idea is that you make a public commitment on the website and a money pledge to a cause or an individual in the case that you fail to keep to your commitment – be it to exercise regularly, give up smoking, save money, or any other personal goal.

Making commitments specific and ownable

One study of environmentally friendly behaviour (with over 2,000 people) looked at the impact of hotel guests’ commitment to practice such behaviour during their stay. Although the commitment was only symbolic, making a brief but specific commitment at check-in made guests 25% more likely to hang at least one towel for reuse and an overall increase of 40% in towels hung.

Two interesting findings from this study were that specific commitments had more impact than general commitments and led to other environmentally friendly behaviours that were not part of the commitment itself (for example, switching off lights).

In another experiment, people were asked to save energy in different ways. One group were just told to “save energy”. A second group were told to “save 20% energy”. And a third group were told to “choose your own energy savings target” – interestingly, the average target chosen was 20%. The first group made 9% savings, the second group made 18% savings (just below the target), and the third group made 22% savings.

Make it public and an active choice

Kurt Lewin was arguably one of the earliest psychologists to think like a behavioural economist. Back in the 1930s, he noticed that making public commitments “freezes” attitudes in place, perhaps anticipating the impact of social media on behaviour?

The experimental evidence shows that commitments work, especially when you apply the following three rules:

- Require the person to take action as the more effort that is required the bigger the impact on future behaviour (as long as it doesn’t stop them making the commitment).

- Make sure the commitment is made in “public”, as that makes it much more powerful (as Kurt Lewin observed).

- Be mindful of the difference between internal motivation and choices and external restrictions. Make the commitment an active choice and avoid rewards and threats. For example, “I don’t litter” is better than “I can’t litter”.

Do commitments work across cultures?

One study compared the impact of commitment/consistency and social norms in the United States and Poland, countries differing in their individualist-collectivist orientation. University students (who else?) were asked to participate in a marketing survey without pay, with half asked after considering information about their own history of compliance with other requests, and half asked after considering information about their peers’ history of compliance.

The commitment/consistency principle had a greater impact on Americans and the social proof principle had a greater impact on Poles, although both principles were influential in both countries.

Ownership, effort, and progress

We value things more when we feel we own them, even if that ownership is perceived rather than real. Just allowing people to touch an item in store increases the likelihood of purchase. We also value things more when we have spent time and effort building them or when we see ourselves progressing towards a goal.

An experiment in Kenya shows a great example of this effect at work. The study focused on how to encourage people to save money. In poor countries, every day can be a crisis with its own needs, and the goal was to find a system that helped people to save rather than simply acknowledging that it is a good idea in principle.

The study compared different incentives to encourage families to save 100 shillings a week (about one US dollar). Five incentives were tested:

- Every little helps. For every 100 shillings saved, families were given a bonus of 10 shillings (pro-rated).

- The child is father to the man. Parents were sent text messages as if they came from their children.

- Bigger bonus. For every 100 shillings saved, families were given a bonus of 20 shillings (pro-rated).

- Pre-match play. Earnings were advanced into family accounts, and if the families saved less a pro-rated deduction was made.

- Coin craft. Families were given an oversized coin to mount on the wall of their hut. They scratched a record of their savings on the coin with a knife (vertical if successful; horizontal if not).

Coin craft was the winning approach, helping families to save almost 1,500 shillings over a 24-week period.

Another experiment with late payers of car tax showed that using a picture of someone’s car number plate (taken from a traffic camera) with a message of “pay your tax or lose your car” led to an increase in payments compared with a standard warning letter.

That feeling of control

Status quo bias shows us that doing nothing and keeping things the same are often the default (because of inertia and avoidance of anticipated regret from changing). However, sometimes people have an impulse to act to gain a sense of control. For example, we often opt for a medical treatment even though the effectiveness is unclear and goal keepers feel the need to jump left or right even though statistically they are better off just staying in the middle of the goal

In this spirit, only about 100 of 1,000 crosswalk buttons in New York really work, acting as placebo buttons to provide the “illusion of control”. Similarly, many “close door” buttons in elevators do nothing (there is a pre-determined timing) and increasing numbers of hotel thermostat dials limit temperature settings to save energy.

Self-determination theory

Dan Pink’s Drive discusses the role of autonomy, mastery and purpose in motivating people. The book has its origins in self-determination theory (which also highlights the importance of relatedness) and other research. Dan Pink defines these three motivators in this way:

- Autonomy: desire for self-direction and control

- Mastery: the urge to improve skills

- Purpose: desire for meaning and importance

Their role is highlighted in an experiment in a nursing home, where residents were split into two groups:

- Group 1 were given a speech and more importantly a greater degree of autonomy by, for example, asking them to take care of a houseplant and giving them a choice of movie night.

- Group 2 were given a similar speech but less freedom and control as they were told houseplants would be taken care of by staff and were pre-assigned a night to watch a movie.

The results showed that residents in the first group were more cheerful, active, and alert. More importantly, 18 months later mortality rates in this group were half of those denied more control over their lives.

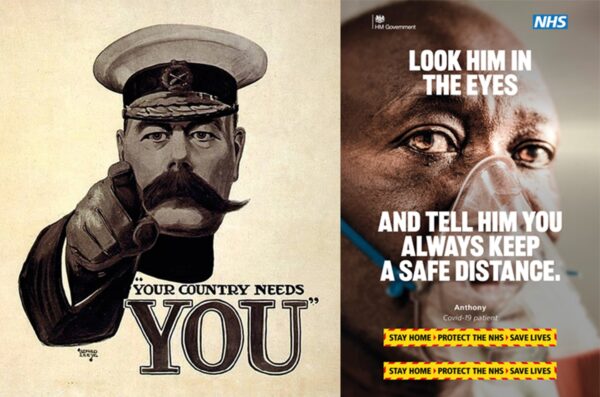

Identify with the person

We all respond to appeals to our own identity. One study of voting compared subtle differences in linguistic cues in appeals for people to vote, looking at nouns (reflecting personal identity) versus verbs (indicating action). Using personal identity (“I am a voter”) was more effective than invoking behaviour (“I vote”).

Personal identity not only increased interest in registering to vote. In two state-wide elections in the United States, using personal identity increased voter turnout based on official state records.

It’s all about you

We all have a view of ourselves at the important aspects of our identity. We like to maintain a view of ourselves that is consistent over time which is why commitments can have such a powerful effect on our behaviour. We also value those things to which we feel an attachment, which is why increasing perceptions of ownership can also have a powerful effect.

Our self-identity and our feeling of autonomy and independence are important to us, even in cultures where social norms are more prevalent (take Thailand for instance). If you want to change someone’s behaviour, there is no better place to start than their sense of themselves.