In the fourth article in our series on mental heuristics and SNAPP we focus on all things personal (click for previous articles on simplicity, norms and availability). The use of plastic is a huge issue for sustainability. Some countries (and individual retail stores) have tried to tackle this issue by charging for using plastic bags. This has generally been more effective than giving a rebate for bringing your own bag. Giving a rebate is a gain but losing the same amount has more impact.

The pain of loss

The idea that losses motivate more than gains is at the heart of Prospect Theory, the foundation of Kahneman and Tversky’s work in behavioural economics. For example, plastic bag use fell by 1 billion in the UK when a 5 pence charge was first introduced. Plastic bag use has continued to fall, with a 95% decline in the main supermarket chains, although the majority of UK supermarkets continue to increase their total plastic use.

Are there smarter ways of reducing plastic bag use without introducing charges? Recent studies suggest that asking the right question when people check out may be as effective as charging.

Charging the use of plastic

One experiment manipulated the framing of a question about bag use at the shop check-out till. Most grocery stores in England frame the question as, “How many plastic bags do you need?” (let’s call this the default question). The experiment used the following alternative strategies:

- “How many plastic bags do you need?” (default)

- “Will you be bringing your own bag to the store?” (conveying an expectation)

- “Will you not be bringing your own bag to the store?” (opposite expectation)

The first two options were also combined with a 5p charge or no charge.

Results showed that plastic bag use was reduced equally by either charging 5 pence, or by using the yes/no question format. In these conditions, 16% or 17% of people took a plastic bag compared with nearly 63% with the default question. Combining the yes/no question with the 5 pence charged reduced plastic bag use to 6%. Those who paid 5 pence also reported lower levels of guilt than those who did not, indicating that charging may potentially crowd out intrinsic motivations to bring your own bag for some people. Put another way, asking the right question is much less painful than invoking loss aversion.

“Losses loom larger than gains”

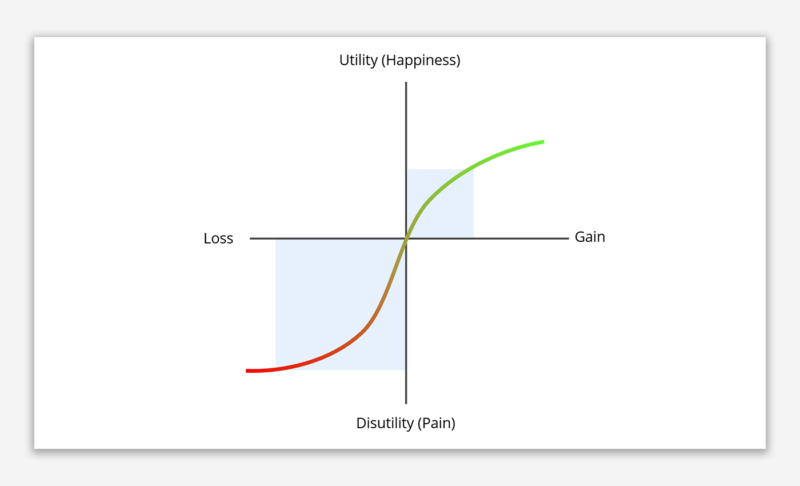

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky identified that we feel the pain of a loss more than the joy of a similar gain, and that this can have perverse influence on our risk-taking behaviours (we are more willing to take risks to avoid a loss than to make a gain in many situations).

This is why penalty frames are sometimes more effective than reward frames in motivating people and people pay more attention to negative information. As Adam Smith, the first behavioural economist, wrote, “We suffer more … when we fall from a better to a worse situation, than we ever enjoy when we rise from a worse to a better.”

The Prospect Theory

The Prospect Theory was developed by Kahneman and Tversky in 1979 and challenges the expected utility theory developed by John van Neumann and Oskar Morgenstein in 1944. It remains a founding theory of behavioural economics and behavioural finance. The theory was built using experimental methods and controlled studies that describe how individuals assess losses and gains in an asymmetric manner. The Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Daniel Kahneman in 2002 specifically because of the experimental approach to building the theory (Amos Tversky died in 1996).

The theory starts with the concept of loss aversion and the observation that people react differently between potential gains and losses, depending on their specific situation rather than in absolute terms.

- Faced with a risky choice leading to gains, individuals are risk-averse, preferring solutions that lead to a lower expected utility but with a higher certainty.

- Faced with a risky choice leading to losses, individuals are risk-seeking, preferring solutions that lead to a lower expected utility if it has the potential to avoid losses.

Putting, prices, and pizzas

What are the practical implications of the theory? There is an interesting story from the sport of golf, an individual sport where every shot counts. However, the evidence shows that some shots count more than others. An analysis of 2.5 million putts from tournament golf showed that there is a 3.6% difference in success rates between putting for a par and putting for a birdie. Golfers try harder when putting for par.

Failing to make par is perceived as a loss, whereas failing to get a birdie is a foregone gain (and not a loss). To a top player like Tiger Woods, equal success in putting for a birdie would increase their average tournament score by one stroke (worth an extra one million dollars per year in prize money).

Consumers are more responsive to price increases than decreases. For example, from July 1981 to July 1983, a 10% increase in the price of eggs led to a 7.8% decrease in demand, whereas a 10% decrease in the price led to a 3.3% increase in demand.

Losses and gains are important in designing menus too. In one study, consumers were asked to either build up a basic pizza by adding ingredients (e.g., sausage and pepperoni), or scale down from a fully loaded pizza by removing ingredients. Consistent with loss aversion, consumers in the subtractive condition ended up with pizza that had significantly more ingredients than those in the additive condition, with a consequent difference in revenues.

Persuading people to keep appointments

Missed appointments are common and costly in healthcare systems, and many hospitals and surgeries are turning to nudges to reduce their impact. St Vincent’s Hospital in NSW, Australia had 15% of outpatients missing appointments, despite a standard reminder. They ran two trials with 7,500 people involving 20,000 text messages in total. The winning message led to a 19% reduction in missed appointments, saving $68,000 per year. The winning message combines loss aversion with a social message:

- You have an appointment with Dr [XXXX] in [clinic XXXX] on [date] at [time]. By attending, the hospital will not lose the $125 that we lose when a patient does not turn up. This money will be used to treat other patients.

Other healthcare studies show mixed success for loss-framed and gain-framed messaging, depending on the seriousness of the disease/treatment and the perceived level of risk (as discussed earlier, perceptions of risk change with the likelihood and seriousness of losses). We take bigger risks when the gains are high but unlikely or when the losses are high and likely.

Too much (negative) information

Negative information receives more processing and is more influential than positive information, a phenomenon known as the positive-negative asymmetry effect. We all react more to changes than to stable conditions, bad events wear off more slowly than good events (and sometimes never at all), positive and negative communication have different impacts on relationships, and negative information has better memory recall. It is worth noting that there are many more words for negative emotions than there are for positive emotions.

Finally, loss aversion does show cultural differences, and one study across 53 countries indicated that individualism, power distance and masculinity (assertiveness) tended to increase loss aversion (as measured by a series of lottery-type questions). Loss aversion was also related to the distribution of major religions in a country, whereas economic variables did not predict loss aversion.

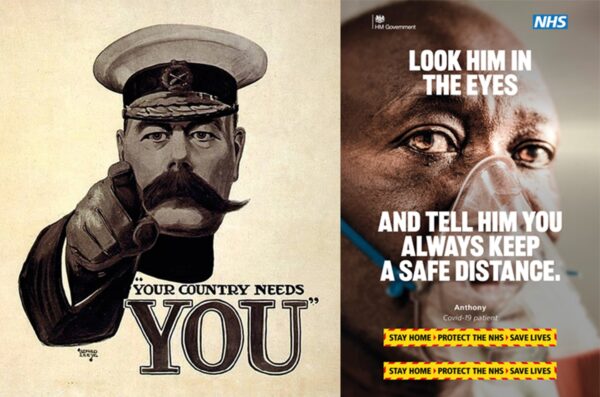

Loss aversion is an important human heuristic to understand, with huge implications for the framing of communications. In the next article, we will continue the discussion of making things personal and relevant with a focus on personal identity, commitment and consistency.

Making It PERSONAL and Relevant (Part 2 – Commitment, Ownership, and Personal Identity) – TapestryWorks

[…] explored the role of loss aversion in behaviour and its potential role in behaviour change (read it here). In this article, we continue with the importance of understanding the role of the personal […]