In previous articles (here and here), I introduced TapestryWorks’ SNAPP framework which covers a wide range of principles from behavioural economics and applied psychology that can be applied to behaviour change. The framework contains five principles, and this and subsequent articles will explore each principle in more detail, especially focusing on applications to social change and sustainability.

The first principle is SIMPLICITY. The brain is lazy and we are all ‘cognitive misers’. It is important to make behaviour change as easy as possible and remove barriers and friction. Communications should be clear and simple (and so many have not been, especially during the pandemic). It is also important to reduce and simplify choices, sometimes by structuring them, to help make decision-making easier.

The limitations of the mind

One of the more quoted papers in the history of psychology is by George Miller on the “magic number 7 +/- 2”. His research was based on presenting people with different shapes and sensations and asking them to rank or order them, but the basic idea of the research has been repeated in many subsequent studies that show that our (conscious) mind has a very limited capacity (unlike our non-conscious mind).

Making (conscious) decisions has a psychological cost and multiple decisions can lead to decision fatigue, diminished self-control and poor choices. It is easier to process simpler information (‘processing fluency’) and, in research, it is much easier for people to ‘recognise’ than to recall (which is why visual tasks work so well). This has some important (if superficially trivial) consequences:

- A factual statement is perceived as more truthful when it is in an easy-to-read font.

- Words that are easier to say or read are more trustworthy and valuable.

- Rhymes and repetition increase memory and ease of understanding (also an example of patterns – watch for a later article).

What is getting in the way?

On the other hand, physical and psychological barriers can stop us doing things even when they are in our interests (and sometimes, thankfully, when they are not). The importance of removing barriers and friction is demonstrated by an example of the UK Behavioural Insights Team’s (BIT or “Nudge Unit”) work. In the UK and other colder countries, uninsulated roofs account for 25% of heat loss from a house.

Insulating a loft costs a few hundred dollars, but immediately reduces bills substantially, with a typical payback period of one or two years. The UK government had used generous finance schemes to encourage families to take out loft insulation and cut their use of energy. Research showed that one of the biggest barriers to uptake was the “pain’ of clearing their lofts.

The Nudge Unit ran a pilot test with a commercial insulation provider with 3 offers:

- A home insulation service at a low, but standard cost.

- A home insulation service with a substantial extra discount if neighbours also booked the same service (with the idea that it was cheaper for the installer to do a couple of houses at once, and participation more likely if a neighbour encouraged you).

- A home insulation service combined with a loft clearance service, with a significant extra cost.

Surprisingly, the second offer made almost no difference to adoption rates, even with the generous discount. However, the third offer had three times the take up, despite costing several hundreds of pounds more. In a later variation of the test, loft clearing was provided at cost, to reduce the total price, and uptake increased by a factor of five.

A great example of using creating barriers to stop certain behaviours comes from my home county of Devon in the UK, where several seaside towns used hedgerows and signs to almost completely eliminate suicide jumps from clifftops.

Smooth riding

The ancient Romans understood the importance of frictionless trade and making movement easy by building a network of straight and fast roads across their empire. 2000 years later, technology is often the key to eliminating friction and making many behaviours easier, simpler, and more convenient.

My first experiences with music where of making my own mix tapes on cassettes (which I have to confess I recorded direct from the radio, training a trigger finger which came in useful when I learned to type). The introduction of CDs was a boon, as I only had to take the CD out of its case, open the player and push and play. I later learnt to create my own playlists, although now all anyone needs to do is log in to a streaming service and choose an existing playlist. I haven’t yet adopted voice activated devices, but all I would need to do now is speak to my speakers.

Jeff Bezos once said, “When you reduce friction, make something easy, people do more of it”. One way to reduce friction is to link a new behaviour to an existing one.

Many people brush their teeth but fail to floss and in one UK study participants flossed 1.5 times per month on average. Participants were given information encouraging them to floss more regularly. Half were told to floss before they brushed their teeth at night and half were told to floss after they brushed their teeth at night. Each day for four weeks they reported by text if they had flossed the night before.

At the end of the month of reminders, they had all flossed about 24 times on average. Eight months later, there was a different story. Why the difference? Those who flossed after brushing, were flossing about 11 times a month, while those who flossed before brushing, were flossing about once a week (4 times a month). Linking flossing to the existing behaviour of brushing helped create a more lasting habit.

Information in bit size pieces

Although George Miller argued that the brain’s capacity is 7 +/- 2, most experts agree that in terms of ‘bits’ of information it is better to stick to 3 or 4 as a maximum. The principle of “chunking” information into 3-4 bite-size pieces is commonly applied in the design of communications and also in menu boards in fast food outlets (for example).

The USDA Food Plate (called MyPlate) is a good example of this. It was adapted from the Food Pyramid, presenting a simpler graphic of a plate divided up. Research on one early version of the plate showed much better recall of details than from the more-complicated Food Pyramid, especially over the long-term (62% recall one-month later versus less than 1% for the Food Pyramid). The conclusion is that it is better to sacrifice the precision of dietary recommendations to provide simple, memorable, and motivating messages.

Simpler feedback for positive outcomes

Another example of simplicity is the Shapa scale developed by a team including Dan Ariely. The scale measures your weight but does not display it. Instead, the scale and associated app record your body mass, including estimates of bone density and muscle mass, and looks at the broader context of changes in body weight over multiple weeks. Feedback is based on a five-point scale, looking at significant trends in weight rather than day-to-day fluctuations.

While, people who step on a scale every day also tend to lose weight, they can be influenced by day-to-day fluctuations, creating a negative experience and association if there is disappointing feedback from one day to the next. In reality, our weight does not react quickly to good and bad behaviours, changes take place over longer time periods, and receiving negative feedback can be demotivating. Dan Ariely writes that in initial trials of the new scales, people who used this scale all lost weight, while those on a standard scale were equally likely to gain weight.

Less is more

When P&G reduced the number of Head and Shoulders SKUs from 24 to 15, their total sales went up by 10%. This has been repeated in other categories and by other companies. As Barry Schwartz writes in The Paradox of Choice, “The fact that some choice is good doesn’t necessarily mean that more choice is better.”

The most famous experiment in this field involves different jam flavours. Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper published a remarkable study of the impact of choice on interest and ultimately purchase decisions. On one day, shoppers at an upscale food market saw a display table with 24 varieties of gourmet jam. Those who sampled the spreads received a coupon for $1 off any jam. On another day, shoppers saw a similar table, except that only six varieties of the jam were on display.

The large display attracted more interest than the small one. But when the time came to purchase, people who saw the large display were one-tenth as likely to buy as people who saw the small display. For many of those exposed to the larger display, the easiest choice was “no choice” when it became too hard to decide. Having choice does give us a sense of control, but sometimes we assert our control by doing (choosing) nothing.

Designing for the ‘right’ choices

We have written previously about the use of choice architecture (a phrase coined by Thaler and Sunstein to describe “organizing the context in which people make decisions”) to influence meal choices. Researchers at Cambridge University analysed 94,000 meal choices across different cafeteria, with data on purchase traceable to individual students (who were paying with university cards topped up with credit). They manipulated the menus in the cafeteria to offer different numbers of vegetarian and vegan food options (from zero to 3 in 4 choices).

The biggest effects were seen in moving from one to two choices leading to between 40% and 80% increases in meat-free choices, with the biggest changes among more carnivorous eaters. Given that meat diets are leading drivers of species loss and climate change, this is a significant result. As one of the study authors writes, “Education is important but generally ineffective at changing diets. Meat taxes are unpopular. Alerting the range of available options is more acceptable and offers a powerful way to influence the health and sustainability of our diets.”

Many different ways have been identified to structure choices:

- Reducing the number of options (e.g., savings plans)

- Staging decisions (often used for longer search processes)

- Defaults (e.g., setting “opt in” defaults for organ donations)

- Technology as a decision aid (mobile apps and smart energy grids)

- Changing time windows (e.g., decreasing time window to use gift cards)

- Chunking information (sometimes called partitioning, as in restaurant menus)

- Rescaling and recalibrating (e.g., reframing credit card repayments)

- Changing labelling to focus on specific times of information (e.g., nutrition)

- Design of environment (e.g., food menus and physical placement of food items)

- Elimination by aspects (highlighting key features as in hotel and flight bookings)

Decisions are hard work, so make them easier

Much of decision-making focuses on what is “good enough” (satisficing in the words of Herbert Simon). Optimising our decisions takes effort and time. Also, it is often more important to avoid bad decisions than to choose the best option, so we often focus on reducing variability of outcomes and uncertainty. Life is much more about ‘desire paths’ than about following cost-benefit calculations. If a particular path gets you to where you need to be quickly and simply, then go with the flow.

Leveraging Social NORMS for Change – TapestryWorks

[…] the SNAPP framework’s five principles I will focus on the importance of social norms (click here to read about simplicity). This principle includes social proof and the reasons we imitate others, […]

Increasing Mental AVAILABILITY for Change – TapestryWorks

[…] I will focus on the importance of mental and physical availability (read about simplicity here and norms here). This principle includes the importance of mental associations that are immediate, […]

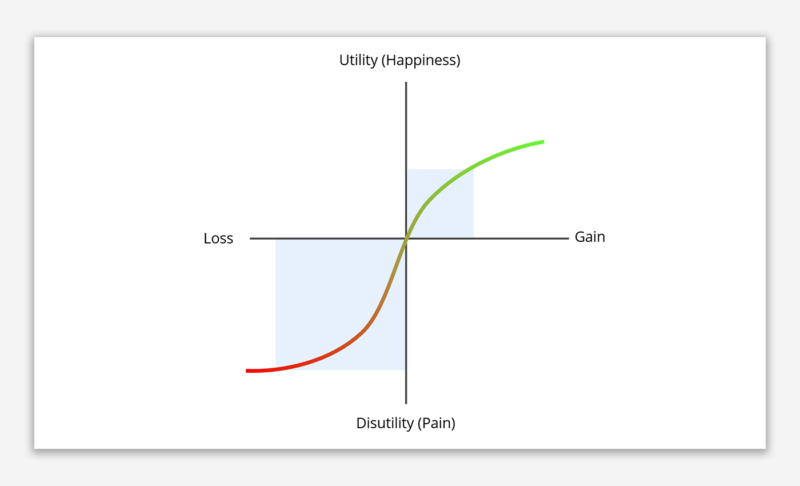

Making It PERSONAL and Relevant (Part 1 – Loss aversion) – TapestryWorks

[…] on mental heuristics and SNAPP we focus on all things personal (click for previous articles on simplicity, norms and availability). The use of plastic is a huge issue for sustainability. Some countries […]