In this series we have talked about the importance of Simplicity, Norms, Availability, and Personalisation twice. Perhaps the brain’s greatest skill is its profound ability to recognize familiar patterns in the world. The brain actively seeks out such patterns, even when they do not really exist (e.g., the man on the moon).

Pattern recognition lies behind many mental heuristics, such as framing and anchors where relative differences matter much more than absolute values. Language can also trigger frames of reference, but the most powerful signals come from sensory experience, and how we perceive the world through vision, hearing, touch and flavour (smell and taste). Gamification is also a way to use patterns to create a sense of fun.

Upsizing or downsizing?

The most striking example of the importance of patterns is the impact on the health of more people in more countries (including in Asia) from increased food consumption. For example, the average American restaurant meal is more than four times bigger than it was 50 years ago.

Many restaurants still “supersize” as do supermarket food packaging. Thinking more domestically, there has also been an increase in the sizes of plates, bowls and glasses in the home (some estimate that the average surface area of a plate is one-third bigger). Many experiments have shown that these changes make a difference in total food consumption.

However, the solution may be equally straightforward: buying smaller pack sizes (or creating single size portions), splitting orders in a restaurant or going without a starter or dessert, and replacing larger tableware with smaller sizes.

Expectations shape experience

Sensory experience is driven by “top down” processing in the brain, which uses knowledge of the past to anticipate future experiences. That’s why the placebo effect is so powerful, showing that the brain’s reward system drives anticipated pleasure (often before the pleasure itself actually happens).

The opening words of the Dhammapada say, “What we are today comes from our thoughts of yesterday, and our present thoughts build our life of tomorrow: our life is the creation of the mind.” The placebo effect was discovered in World War II by accident, when morphine supplies were low and an enterprising nurse tried injecting a badly wounded patient with a saline solution, immediately calming him down. The nurse worked with Henry Beecher, who then repeated the trick many times and returned to America to study why it worked at Harvard.

One experiment on the relationship between exercise and health, also looked at the impact of mind-set. Female room attendants working in different hotels were measured on physiological health variables affected by exercise. They were split into two groups, with one group informed that their work was good exercise and satisfied recommendations for an active lifestyle (the “informed condition”) and a second group were not given this information (the “control condition”).

During the period of the trial, actual behaviours did not change, although after four weeks the informed group perceived that they were getting significantly more exercise. More surprisingly, they also showed decreases in weight, blood pressure, body fat, waist-to-hip ratio and body-mass index. Potentially this shows that exercise works partly through a placebo effect.

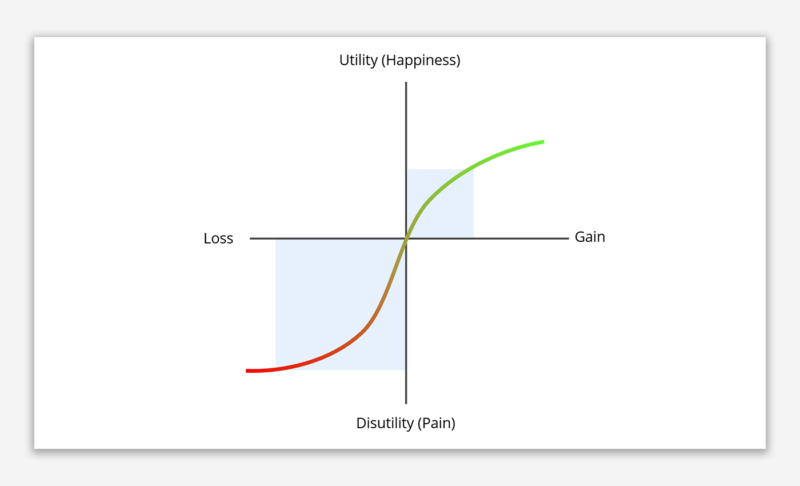

Everything is relative

Everything is relative to the mind, which is why the same information can be framed in different ways (e.g., losses vs gains) to change impact. The centre-stage effect (also called the “Goldilocks effect”) is based on our preference for options that are positioned, priced or sized in the middle. Decoys are options that are similar to but less attractive than a similiar option, changing overall preferences.

How names make vegetables desirable

What sounds better? A baked potato or a loaded potato feast? Decadent sounding descriptions can increase vegetable consumption, while “healthy” foods are perceived as less tasty and less satisfying. In one of many experiments on this theme, indulgent names increased consumption relative to basic descriptions, healthy restrictive (e.g., “light”, “low-carb”), and healthy positive (e.g., “healthy energy boosting”).

As well as “healthy”, labels such as “meat free”, “vegetarian”, “vegan”, which are often interpreted in terms of self-identity as well as description, encouraging responses such as “that’s different from me” as well as “healthy means less tasty”. An alternative is to use labels which invoke provenance, flavour and overall look and feel.

How language changes health behaviours

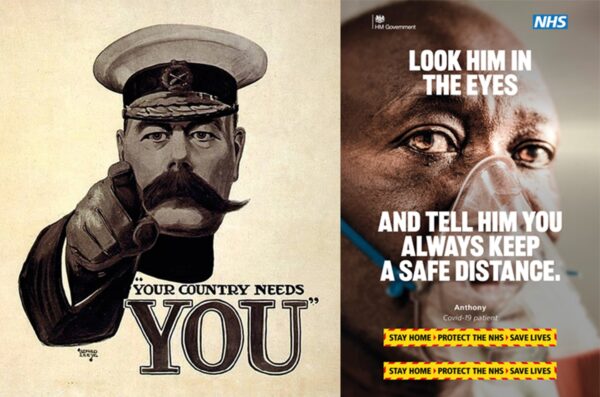

The ability of language to frame messages and behaviours has been demonstrated very clearly during the Covid-19 pandemic. Waarfare is a popular metaphor and was much used in pandemic messaging (e.g., “fighting the coronavirus”, “Covid warriors”). It is also popular in the hygiene category (e.g., “kills 99% of germs”), but does imply an enemy (in this case an invisible one).

Wars need soldiers to fight the enemy, and without. The right weapons people can feel helpless or look for other enemies. The need for autonomy can also lead to psychological reactance, a negative reaction to the message and its meaning (consider the success of the “war on drugs”).

Arguably, sokidarity has been a more useful metaphor in many countries, as the virus cannot be “beaten into submission” and we need to learn to live with it. The best survivial strategy is to cooperate not fight.

New Zealand is an interesting example of mixing these metaphors. Athough New Zealand has some geographic advantages (isolated islands) and a small population of 5 million it also has a very diverse, rebellious and freedom-loving population with relatively lower compliance to social norms

They locked down very early and very strictly, rallying people around a central mission of “A team of 5 million people”. Although there was a call to fight “Unite against Covid-19”, the enemy is very clear and it’s not other people.

What you see is all there is?

Apicius said that, “We eat first with our eyes”. For example, different shapes of glass (in one experiment, inward, straight and outward curving) led to faster or slower drinking and differences in the ability to estimate volume.

We also walk with our eyes, and students in Copenhagen used painted footprints and painted bins (bright green) to increase litter put in bins. This trick can also be used to encourage people to walk rather than taking the stairs. Similar approaches have used planting of trees alongside roads to slow down traffic through villages in the UK

Listening to the air

I love the behavioural trick used by the Moscow tube to help vision impaired people navigate the system. Messages come from a male announcer when travelling towards town and from a female announcer when travelling away from the centre. Very simple and helpful for everyone, including those with full use of their eyes.

Music has strong effects on shopper behaviour. Fast music increases table turnover (useful in fast food restaurants) while slower music increases time spent in a retail store. People stay in stores longer for music that they don’t know (although they claim to stay longer for music that they know) and different styles of music can prime different purchases (famously in one experiment, French vs German wine). Finally, classical music is associated with quality!

Touch and take home?

Merely touching an item increases the sense of ownership and likelihood to buy, and can even be invoked with descriptions and words as well as physical touch

The colour of taste

The colour of bowls for serving popcorn has an impact on taste, as does the colour of spoons that you eat yoghurt from. Flavour is also affected by other factors such as weight of of plates and cutlery and even the type of cutlery (food is saltier when eaten from a knife).

Making it fun

Gamification can be seen in many of these experiments and has been applied to behaviour change in different experiments, most notable by “The Fun Theory” with bottomless bins and musical staircases. The great thing about gamification, and a final lesson on using the senses to change behaviour, is how powerful feedback loops are (positive or negative) in shaping behaviour. And if you are feeding back, do it as close to the behaviour itself as possible, This reinforces and encourages people to do it again.

Patterns are a powerful way to use the brain’s strength as a pattern recognition machine to prompt, motivate and reinforce behaviours.