The SNAPP Framework for Sustainable Behaviours

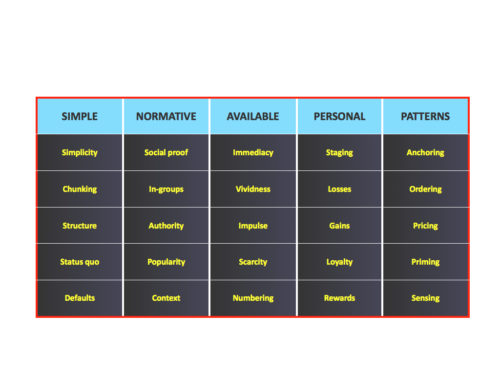

The field of behavioural economics can be confusing, with so many ‘heuristics’ (a better name than biases, Wikipedia lists almost 200) and very few overall guiding frameworks. TapestryWorks developed the SNAPP framework to help guide the application of behavioural science through a number of key themes and ideas that appear frequently and link many heuristics through underlying principles.

SNAPP breaks down these mental rules of thumb into behavioural triggers and barriers that fall into five key themes that drive decision-making. These are the need to keep things SIMPLE, the desire to follow social NORMS, a preference towards mental AVAILABILITY, a focus on keeping things PERSONAL and the brain’s need to find PATTERNS in the world.

Keeping it SIMPLE

Our brains love simplicity, even if we like to think that more choice and greater complexity is better. Our brain is lazy. Better stated, our brain is efficient and likes new behaviours to be easy to adopt with as little friction as possible. Barriers can be physical or mental, and simplifying choices and structuring choices helps decision-making.

For example, in colder countries, an uninsulated roof typically accounts for 25% of heat loss from a house.Insulating a loft costs a few hundred dollars, but immediately reduces bills.

The payback period for loft insulation is typically one or two years. The UK government tried using generous finance schemes to encourage families to take out loft insulation and cut their use of heating energy (and their bills too). Research showed that the biggest barrier to uptake was the pain of clearing their lofts.

The UK Nudge Unit ran a pilot test with a commercial insulation provider with 3 offers:

- A home insulation service at a low, but standard cost.

- A home insulation service with a substantial extra discount if neighbours also booked the same service (with the idea that it was cheaper for the installer to do a couple of houses at once, and participation more likely if a neighbour encouraged you).

- A home insulation service combined with a loft clearance service, with a significant extra cost.

Surprisingly, the second offer made almost no difference to adoption, even with the generous discount. However, the third offer has three times the take up, despite costing several hundreds of pounds more. In a later variation of the test, loft clearing was provided at cost, to reduce the total price, and uptake increased by a factor of five.

Leveraging Social NORMS

Humans are social animals and follow social customs and cultural norms. We imitate the behaviours of others and look to others for a lead. We return favours and don’t like it when others violate social norms. And our humanity is very important to us and can be prompted. Intrinsic motivations can be more powerful than financial incentives. In the words of Dan Ariely, “Money is very often the most expensive way to motivate people. Social norms are not only cheaper, but often more effective as well.”

Use of social norms has increased in recent years. In Singapore and many other countries, energy and water bills compare household consumption to other households, most powerfully when the comparison is your next-door neighbor. Some empirical studies show that such interventions should be carefully designed, as they set bad as well as good norms. If you are told that a neighbour uses more electricity than you, you may actually increase consumption.

Sustainability and Mental AVAILABILITY

Behaviours are more likely when they are ‘top of mind’. That’s why it is so important to be salient and relevant and to stand out from the crowd. The biggest challenge for sustainable behaviour is the immediacy of the pleasure of gratification and the pain of payment compared with benefits that are in the distant and remote future.

However, instant gratification can be a good thing if is linked to a positive sustainable outcome. For example, it is very easy to spend money on impulse, but one American bank developed a phone app that allowed instant saving. It helped give customers an easily accessible trigger for saving money when they felt in the right mood. Another bank used the insight that people often round up when they pay bills to make a ‘rounding up’ default for automatic payments, so the balance went to the customer’s saving account.

Making Sustainability PERSONAL

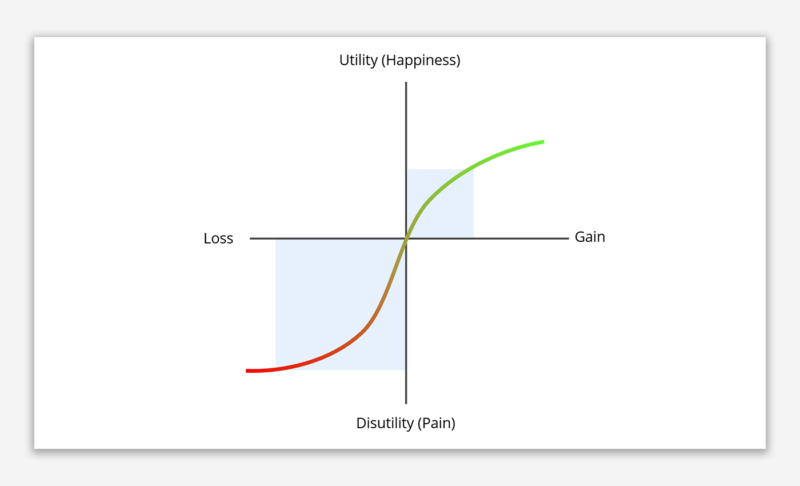

One of the keystones of behavioural economics is the concept of loss aversion, for which Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel prize in economics. It relates to many other behavioural traits such as the power of commitments and the importance of consistency to our self-image. We also like to feel a sense of ownership and progress in our lives.

Loss aversion is an important consideration in reducing the use of plastic in the world, as seen in laws passed in the UK and more recently in Thailand. Although many countries and retail chains have tried giving rebates for people who ‘bring their own bags’, penalizing people by charging for plastic bag use has often been shown to be more effective.

In the UK, shoppers are charged 5 pence (~2 Baht) for each plastic bag they are given at checkout and plastic bag use has fallen by 1 billion in 3 years (from 2.1 billion in 2016-17 to 1.1 billion in 2018-19). In addition, many businesses have used the proceeds to support good causes (more than GBP 23 million). Losses often motivate more than gains.

Sustainability and PATTERN Recognition

The brain is a pattern recognition machine, and finds patterns everywhere, even when they don’t really exist. This speaks of the power of the senses to trigger behaviour and as our source of information about the outside world. Patterns are also important because perception is relative. Context is very important to the brain’s predictions and we focus on first impressions and initial information to provide a frame of reference. The importance of patterns is also why expectations are often more important than the reality of experience.

Creating engaging sensory experiences can encourage sustainable behaviours. Making staircases play musical notes or even creating a colourful path up the stairs can encourage people to walk instead of using a lift or escalator.

Placebos are the most powerful form of expectation overcoming reality. In one experiment, merely telling hotel maids that their work was providing good physical exercise not only led them to believe they were getting more exercise, but led to decreases in weight, body fat and blood pressure relative to a control group.

A Framework for Sustainability

SNAPP provides five important principles that can be applied to develop more sustainable behaviours:

- Keep it SIMPLE

- Use Social NORMS

- Increase Mental AVAILABILITY

- Make things PERSONAL

- Manage Expectation with PATTERNS

Shaping Behaviour in a Crisis: SNAPP Behaviour and Covid-19 – TapestryWorks

[…] is based on a behavioural economics framework comprising five key themes (read more here and here) and has been applied to pricing, sustainability and other […]